Monday, November 27, 2006

Saturday, November 11, 2006

Alan Warner on writing

TimeOut London

June 5th, 2006

Is there anything unique about the way I write? Well, I feel so incredibly ill-disciplined, and I have a kind of paranoia that all other writers are very disciplined. I don’t write at any set times; I just write when it takes me. When things are going well I’ll go for 12 hours, but when things are going badly I’ll just look out the window. I think the basic rule is that if nothing’s coming then nothing’s coming. It’s really hard to force stuff for me – it’s that Hemingway thing. Now, he used to write standing up, but I think that was because of his haemorrhoids, so I can understand that. Not that I’m a sufferer; it’s one of the few afflictions I’ve been spared. So far.

When things are going badly, I sometimes flit between the book and email. Which is deadly, but I’ve more or less stopped that. I noticed for a while that I was going into my study and dedicating far too much care to my angry letters to the electricity company: ‘The Collected Letters to Scottish Power’. I should return to that opus one day.

I know a lot of writers listen to music when they write and I do too, but it has to be ambient or something like that. If you have something you really like on, the music can add a soundtrack to what you’ve just written and you can think it’s much more interesting or dramatic or moving that it is.

Could I conceivably have a day job? Not any more. I’m too fat and spoiled, I’m afraid. The first novel I wrote was completely done between night shifts working on the railways in Scotland. I stopped going out and just worked on the book. But the shifts were quite good discipline because you knew you only had those hours. Once they stopped and the luxury of time arrived, I’m sure my work ethic crumbled quite a bit. Fiction feeds off the life you’ve led or are leading. I think that’s why so many novels in England used to be, or still are, dull.

A lot of writers would just come down from Oxbridge and land a good office job – not digging roads or anything – so for many years there was a kind of predictable sheen on every writer’s life experience. American literature comes out so rich because there are so many different lived experiences out there, so many cultures. Even in the 1950s you had your Cheevers and Updikes – urbane New York – alongside the Beats, living a completely different kind of life. And writing about it in a way that, at the time in Britain, was almost inconceivable.

The romance of being a writer diminshes. It was more romantic when I started out ten years ago. And that romance itself is rather limited; it’s a space in your own mind. It hits suddenly one day in the pub – say, by yourself on a Tuesday with a pint of Guinness. You go, ‘Ah, for my next novel, what I might do is…’, and you look at yourself and go, ‘Wow, Warner. You’re in the pub going, “For my next novel…” ’ And that’s quite romantic. Or you’re in a café and some friend introduces you as ‘Alan, the writer’. Boom. But I don’t think of myself as a writer. I think of myself as a reader. Or a skiver.

Alan Warner’s new novel ‘The Worms Can Carry Me To Heaven’ is published by Cape

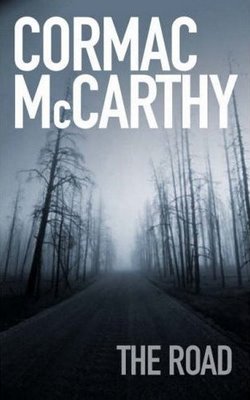

The Road, by Cormac Macarthy

After the sparse, stripped-down prose of No Country For Old Men, Macarthy is back with a chilling post-apocolyptic vision of the future. The following review is from Alan Warner, author of the Scottish existential angst-ridden Morvern Callar. The only thing missing is a mention of William Gay among his Tough Guys.

After the sparse, stripped-down prose of No Country For Old Men, Macarthy is back with a chilling post-apocolyptic vision of the future. The following review is from Alan Warner, author of the Scottish existential angst-ridden Morvern Callar. The only thing missing is a mention of William Gay among his Tough Guys.The road to hell

The Guardian Saturday,

November 4th, 2006

Shorn of history and context, Cormac McCarthy's other nine novels could be cast as rungs, with The Road as a pinnacle. This is a very great novel, but one that needs a context in both the past and in so-called post-9/11 America.

We can divide the contemporary American novel into two traditions, or two social classes. The Tough Guy tradition comes up from Fenimore Cooper, with a touch of Poe, through Melville, Faulkner and Hemingway. The Savant tradition comes from Hawthorne, especially through Henry James, Edith Wharton and Scott Fitzgerald. You could argue that the latter is liberal, east coast/New York, while the Tough Guys are gothic, reactionary, nihilistic, openly religious, southern or fundamentally rural.

The Savants' blood line (curiously unrepresentative of Americans generally) has gained undoubted ascendancy in the literary firmament of the US. Upper middle class, urban and cosmopolitan, they or their own species review themselves. The current Tough Guys are a murder of great, hopelessly masculine, undomesticated writers, whose critical reputations have been and still are today cruelly divergent, adrift and largely unrewarded compared to the contemporary Savant school. In literature as in American life, success must be total and contrasted "failure" fatally dispiriting.

But in both content and technical riches, the Tough Guys are the true legislators of tortured American souls. They could include novelists Thomas McGuane, William Gaddis, Barry Hannah, Leon Rooke, Harry Crews, Jim Harrison, Mark Richard, James Welch and Denis Johnson. Cormac McCarthy is granddaddy to them all. New York critics may prefer their perfidy to be ignored, comforting themselves with the superlatives for All the Pretty Horses, but we should remember that the history of Cormac McCarthy and his achievement is not an American dream but near on 30 years of neglect for a writer who, since The Orchard Keeper in 1965, produced only masterworks in elegant succession. Now he has given us his great American nightmare.

But in both content and technical riches, the Tough Guys are the true legislators of tortured American souls. They could include novelists Thomas McGuane, William Gaddis, Barry Hannah, Leon Rooke, Harry Crews, Jim Harrison, Mark Richard, James Welch and Denis Johnson. Cormac McCarthy is granddaddy to them all. New York critics may prefer their perfidy to be ignored, comforting themselves with the superlatives for All the Pretty Horses, but we should remember that the history of Cormac McCarthy and his achievement is not an American dream but near on 30 years of neglect for a writer who, since The Orchard Keeper in 1965, produced only masterworks in elegant succession. Now he has given us his great American nightmare.

The Road is a novel of transforming power and formal risk. Abandoning gruff but profound male camaraderie, McCarthy instead sounds the limits of imaginable love and despair between a diligent father and his timid young son, "each other's world entire". The initial experience of the novel is sobering and oppressive, its final effect is emotionally shattering.

America - and presumably the world - has suffered an apocalypse the nature of which is unclear and, faced with such loss, irrelevant. The centre of the world is sickened. Earthquakes shunt, fire storms smear a "cauterised terrain", the ash-filled air requires slipshod veils to cover the mouth. Nature revolts. The ruined world is long plundered, with canned food and good shoes the ultimate aspiration. Almost all have plunged into complete Conradian savagery: murdering convoys of road agents, marauders and "bloodcults" plunder these wastes. Most have resorted to cannibalism. One passing brigade is fearfully glimpsed: "Bearded, their breath smoking through their masks. The phalanx following carried spears or lances ... and lastly a supplementary consort of catamites illclothed against the cold and fitted in dogcollars and yoked each to each." Despite this soul desert, the end of God and ethics, the father still defines and endangers himself by trying to instil moral values in his son, by refusing to abandon all belief.

All of this is utterly convincing and physically chilling. The father is coughing blood, which forces him and his son, "in their rags like mendicant friars sent forth to find their keep", on to the treacherous road southward, towards a sea and - possibly - survivable, milder winters. They push their salvage in a shopping cart, wryly fitted with a motorcycle mirror to keep sentinel over that road behind. The father has a pistol, with two bullets only. He faces the nadir of human and parental existence; his wife, the boy's mother, has already committed suicide. If caught, the multifarious reavers will obviously rape his son, then slaughter and eat them both. He plans to shoot his son - though he questions his ability to do so - if they are caught. Occasionally, between nightmares, the father seeks refuge in dangerously needy and exquisite recollections of our lost world.

They move south through nuclear grey winter, "like the onset of some cold glaucoma dimming away the world", sleeping badly beneath filthy tarpaulin, setting hidden campfires, exploring ruined houses, scavenging shrivelled apples. We feel and pity their starving dereliction as, despite the profound challenge to the imaginative contemporary novelist, McCarthy completely achieves this physical and metaphysical hell for us. "The world shrinking down to a raw core of parsible entities. The names of things slowly following those things into oblivion. Colours. The names of birds. Things to eat. Finally the names of things one believed to be true."

Such a scenario allows McCarthy finally to foreground only the very basics of physical human survival and the intimate evocation of a destroyed landscape drawn with such precision and beauty. He makes us ache with nostalgia for restored normality. The Road also encapsulates the usual cold violence, the biblical tincture of male masochism, of wounds and rites of passage. His central character can adopt a universal belligerence and misanthropy. In this damnation, rightly so, everyone, finally, is the enemy. He tells his son: "My job is to take care of you. I was appointed by God to do that ... We are the good guys." The other uncomfortable, tellingly national moment comes when the father salvages perhaps the last can of Coke in the world. This is truly an American apocalypse.

The vulnerable cultural references for this daring scenario obviously come from science fiction. But what propels The Road far beyond its progenitors are the diverted poetic heights of McCarthy's late-English prose; the simple declamation and plainsong of his rendered dialect, as perfect as early Hemingway; and the adamantine surety and utter aptness of every chiselled description. As has been said before, McCarthy is worthy of his biblical themes, and with some deeply nuanced paragraphs retriggering verbs and nouns that are surprising and delightful to the ear, Shakespeare is evoked. The way McCarthy sails close to the prose of late Beckett is also remarkable; the novel proceeds in Beckett-like, varied paragraphs. They are unlikely relatives, these two artists in old age, cornered by bleak experience and the rich limits of an English pulverised down through despair to a pleasingly wry perfection. "He rose and stood tottering in that cold autistic dark with his arms out-held for balance while the vestibular calculations in his skull cranked out their reckonings. An old chronicle."

Set piece after set piece, you will read on, absolutely convinced, thrilled, mesmerised with disgust and the fascinating novelty of it all: breathtakingly lucky escapes; a complete train, abandoned and alone on an embankment; a sudden liberating, joyous discovery or a cellar of incarcerated amputees being slowly eaten. And everywhere the mummified dead, "shrivelled and drawn like latterday bogfolk, their faces of boiled sheeting, the yellowed palings of their teeth".

All the modern novel can do is done here. After the great historical fictions of the American west, Blood Meridian and The Border Trilogy, The Road is no artistic pinnacle for McCarthy but instead a masterly reclamation of those midnight-black, gothic worlds of Outer Dark (1968) and the similarly terrifying but beautiful Child of God (1973). How will this vital novel be positioned in today's America by Savants, Tough Guys or worse? Could its nightmare vistas reinforce those in the US who are determined to manipulate its people into believing that terror came into being only in 2001? This text, in its fragility, exists uneasily within such ill times. It's perverse that the scorched earth which The Road depicts often brings to mind those real apocalypses of southern Iraq beneath black oil smoke, or New Orleans - vistas not unconnected with the contemporary American regime.

One night, when the father thinks that he and his son will starve to death, he weeps, not about the obvious but about beauty and goodness, "things he'd no longer any way to think about". Camus wrote that the world is ugly and cruel, but it is only by adding to that ugliness and cruelty that we sin most gravely. The Road affirms belief in the tender pricelessness of the here and now. In creating an exquisite nightmare, it does not add to the cruelty and ugliness of our times; it warns us now how much we have to lose. It makes the novels of the contemporary Savants seem infantile and horribly over-rated. Beauty and goodness are here aplenty and we should think about them. While we can.

· Alan Warner's latest novel is The Worms Can Carry Me to Heaven (Cape)

Thursday, November 09, 2006

Action woman

The Scotsman - February 9th 2002

From Elizabeth Balneaves’s kitchen window you can see a bird-table all a-flurry with shrill visitors. It’s a cheering sight but somewhat more domesticated than the view she had of the North Rhodesian bush, 40-odd years ago: "The smell of elephant lay heavy in the blazing heat of the afternoon ... a couple of black storks careened down through the treetops to land uncertainly like helicopters on the soft sand … A cloud of Zambesi lovebirds flashed emerald green almost across our faces and a lone baboon roared like a lion from the depths of the thicket."

It’s a far cry from the weekday afternoon lassitude of Cullen, the quiet Banffshire resort where Balneaves now lives; not quite so distant in memory, however, as this disconcertingly vigorous 90-year-old is busy writing her memoirs on the computer her sons gave her for her birthday last September. Balneaves’s main document sorting area is the kitchen table. It is littered with diaries, scrapbooks and photographs - depicting her stooped over a camp fire in the Hindu Kush, or wading in an African river hanging on to what she calls "the nonoperative end" of a sizeable python.

She is surveying her eventful life just as a biography has appeared of another Scots traveller, author and film-maker Isobel Wylie Hutchison. Balneaves herself was friendly with a third adventurer and chronicler, the Shetland-based Jenny Gilbertson, who, like Hutchison, filmed the indigenous peoples of the Arctic circle. All three ventured, often alone, into what was very much men’s territory.

Artist, author, film-maker, Balneaves has led what most of us, save perhaps the terminally adventurous, might describe as a full life. The daughter of an Aberdeen headmaster, she graduated from the city’s Gray’s School of Art in 1934, already engaged to psychologist Dr James Johnston: "We met at Wormwood Scrubs. He was on the staff and my uncle was a visiting doctor there."

At the end of the 1940s, they were living in Edinburgh and she was combining painting with looking after their four children until, as she puts it with a disarming insouciance, she "took off" for Pakistan, and not with her husband. "It’s … um … I’m writing my memoirs just now and it’s rather difficult, but I met this chap and went off with him and by the time I’d decided it wasn’t on, it was too late."

If the emotional attraction proved misguided, the relationship with Pakistan would be a lasting one, and formative - in order to live, she nursed, became temporary head of arts and crafts at the University of the Punjab in Lahore, wrote for Punjab Gazette and helped found and edit the Pakistan Review.

Returning to London, she launched into freelance journalism and promptly landed a commission for a book on Pakistan which sent her back there, taking her own photographs after the arranged snapper fell through. The result, The Waterless Moon, sported a foreword by Sir William Barton, former political agent in Swat and Chitral, describing it as "an extraordinary book, written by an extraordinary young woman of courage and grit … and with all this that rare gift of close observation and the faculty of describing what she sees in vivid language."

Plaudits apart, the book hardly made her fortune and, by this time in her late forties, she started taking photographs for companies involved in hydro-electric power and other schemes in Pakistan. One such job involved clambering up the outside ladder of a water tower. "I managed to get to the top and the German engineer I was with said , ‘Ach, you vomen of today!’ If he’d only known that the woman of today was shaking like a jelly. But I got the photograph."

Another book, Peacocks and Pipeless, resulted. Around that time, largely at the behest of their children, she re-married the long-suffering Johnston who was posted to Carstairs State Hospital. "I had a marvellous time. I taught eight murderers to paint," she says with some glee.

When one of her sons, Stewart, got a job in tobacco farming in what was then Northern Rhodesia, she seized the opportunity and ended up documenting the rescue of animals as, during the late 1950s, the Kariba dam project was flooding a vast area, displacing both people and animals. Her Elephant Valley was about game and tsetse supervisor Joe MacGregor Brooks, who was carrying out a private animal rescue operation of his own.

She returned with her first film camera and also a commission from Edinburgh Zoo, for whom she’d been working as a PR, to bring back some animals. She made a short film for schools television on the capture of an aardvaark: "I edited it in the attic, wrote the commentary and read it. They wanted ten minutes and I think it was just a minute out," she recalls.

Further films followed, articles in The Scotsman and National Geographic, among other journals; there was a return to Pakistan and the Hindu Kush, and another book, Mountains of the Murgha Zerin.

Many of her forays were made virtually alone, or in very much men-only environments. Did she ever feel at risk? "No. I feel more at risk here when someone bashes on my door at half-past 12 at night. The only time I did feel at risk was in Calcutta, where I was burgled one night."

She and her husband moved to Shetland, which prompted another book, The Windswept Isles, and where, through their respective daughters, she got to know the Glasgow-born documentary film-maker Jenny Gilbertson.

Gilbertson had become hooked after seeing amateur holiday film of Loch Lomond and, self-taught, had gone on to make a string of film documentaries about Shetland life at a time when, thanks to the likes of Michael Powell and Robert Flaherty, films about remote communities were becoming popular. Gilbertson emerged from the Scottish hotbed of documentary film making, encouraged by the crusty pioneer John Grierson, who described her first effort, A Crofter’s Life in Shetland, in 1931 as "an extraordinary job of work.

Among Gilbertson’s other films were The Rugged Island, made in 1934 about the life of a Shetland crofter - whom she ultimately married - and a film about Shetland ponies which took her four years to make.

Gilbertson, recalls Janet McBain, curator of the Scottish Film Archive in Glasgow, may have been small in stature, "but she was ten feet tall in action and energy". Gilbertson died in 1990 and the archive now holds much of her material, while seats in both the Glasgow Film Theatre and Edinburgh Filmhouse are dedicate in her name by Shetland Islands Council.

"We had a lot of fun together," Balneaves recalls of Gilbertson. The pair travelled together to Papa Stour, filming the island’s famous sword dance, though the film itself seems to have vanished without trace.

Still feeling that outward urge in her 70s, Gilbertson headed for the Canadian Arctic to film the changing life of the Inuit, among other things documenting the 300-mile journey made by one dog team. Balneaves was supposed to join her on one such Canadian expedition, but caught pneumonia beforehand so Gilbertson, as she did so often, went alone.

Balneaves, for her part, made her last working trip in 1982, after her one-time book subject, Brooks MacGregor, asked for help in publicising elephant poaching in Zambia. "I did 15 miles through the bush, twice, with a game guard - got some super photos of buffalo." She was 71.

Jenny Gilbertson would almost certainly have known, or at least known of, the third and perhaps most remarkable in our triumvirate of doughty Scots women travellers, authors and (all self-taught) film-makers, Isobel Wylie Hutchison.

Brought up at Cardownie, a Scotsbaronial mansion outside Kirkliston, West Lothian, Hutchison grew from a reserved and private girl into a remarkable yet still little-known traveller, botanist, poet, author and film-maker, who between 1927 and 1936 made four major journeys to Greenland, the northern coasts of Alaska and Arctic Canada, at a time when it was rare for women to go any further north than the goldfields of Alaska and Yukon. She brought back botanical specimens, film footage and the makings of several books, including On Greenland’s Closed Shore, North to the Rime-Ringed Sun and Arctic Nights’ Entertainments. Her film footage, held by the Scottish Screen Archive, shows Greenlanders stepping out enthusiastically in Scottish dances taught to them by visiting whalers a century before.

Hutchison, who died in 1982, was an enigmatic combination of the wilfully determined and the near-mystical, seeing the hand of God in the sublime and awesome Arctic environment, and who did much of her travelling alone, or in the rough and ready, all-male company of sailors, trappers and hunters. As Gwyneth Hoyle of Trent University, Ontario, puts it in her newly published biography of Hutchison, Flowers in the Snow (University of Nebraska Press), "Leading a sheltered life in a Victorian home until she was nearly 30, Isobel expanded and blossomed in personality with each new adventure … She was like a flower whose bud remains tightly closed until the right circumstances cause it to open."

She was, as another commentator puts it, "gloriously out of step with the conventions of her time".

Was there something in the air, or the water, that should produce the likes of Hutchison and two other redoubtable Scots women traveller-film-makers within a couple of decades? David Munro, current director of the Royal Scottish Geographical Society, whose journal Hutchison edited for ten years, points out that within the Scottish tradition of producing notable explorers, several of them were women, such as Hutchison, or Ella Christie from Dollar, who travelled on foot from Istanbul into Central Asia and made a similar journey from Moscow.

"We seem to have a remarkably high proportion of women with boundless energy and insatiable curiosity, and that’s a very Scottish trait," says Munro. "In Hutchison’s writings she is always pulled on by what’s beyond the horizon. And she is undaunted by the discomforts, another Scottish trait. And you have these traits balanced against the fact that it was very unfashionable for women to be doing this sort of thing."

The Scottish education system, he reckons, was crucial, "but there was also the social system, with all sots of push-pull factors operating, from the Highland clearances to the claustrophobia of Edinburgh society."

Hutchison assiduously noted domestic details among the Icelanders, Greenlanders and Inuits she visited, what they cooked and how - not the kind of thing you’d find, as Hoyle remarks in her biography, "in the heroic narratives of male Greenland explorers".

Munro agrees that women travellers observe differently from their male counterparts: "With Hutchison you get to meet the people and you encounter the landscape, she notices everything, whereas with many another early travel writer it’s all about them … I can think of writers who don’t even tell you the names of the guys who are carrying the baggage for them."

According to Hoyle, Hutchison would never have called herself a feminist - "merely an independent person who may have observed the bonds of conventional society at home but was prepared to be as unconventional as necessary in her travels". Unconventional all three women’s lives may have been, but they were also long. Elizabeth Balneaves is still rattling away at her computer, a spry 90; Gilbertson was re-editing some of her films within two years of her death at the age of 88; Hutchison was 92 when she died, outliving all her family and most of her friends. Whatever the rigours of going it alone as a woman traveller, it doesn’t seem to require a government health warning.

Elizabeth 'Betty' Balneaves

My grandmother lived a full life until the day she died, November 7th. Just a few short weeks ago she celebrated her 95th birthday with a party at her home - matching the stragglers, my brother Sorley and cousin Tim, with whisky-drinking endurance into the wee hours of the morning. I have decided to return from New Zealand for her funeral in Scotland. Travelling round the world to celebrate her memory seems fitting. She was the most intrepid explorer I have ever known. My father, J Laughton Johnston, wrote the following obituary for The Scotsman (Tuesday 14th November 2006):

Elizabeth Balneaves (1911-2006)

Elizabeth, or Betty as she was known to friends and family, author, painter and filmmaker, was born in Aberdeen, the only child of Annie and Alexander Balneaves. She graduated from Aberdeen Art College and married the psychiatrist Dr James McL Johnston of Shetland extraction in 1934. Although they were separated for several years, Jim supported her in her work throughout their married life.

Betty wrote six books, made a number of documentary films, drew many portraits in pastel and charcoal and painted many landscapes, latterly mainly of Shetland and Cullen. In Shetland, which she first visited with Jim in 1934, she is perhaps best known for The Windswept Isles (1977), which she wrote during the 20 or so years she and Jim lived in retirement in the old manse at Bigton in the 1960s and '70s. This was her tribute to the people and the islands whom she always felt had adopted her.

During those years she also made a documentary film of Shetland for the BBC: People of Many Lands - Shetland. Although painting was her first love it was her writing that brought her to a wider public attention, one of the first signs of her literary talent being a poem published in 1945 in Poetry Scotland (2nd collection), that wonderful series of Scottish poetry books published by William MacLellan & Co.

In the early 1950s Betty travelled alone to Pakistan, particularly to Karachi and the Frontier with Afghanistan , where she stayed for several years, resulting in The Waterless Moon (1955) and Peacocks and Pipelines (1958), both of which received some critical acclaim. Later, she returned to the area with her son, Stewart, resulting in a third book on the area between the Hindu Khush and the Karakoram, The Mountains of the Murgha Zerin (1972) and some unique film footage of this remote area and its culture.

At a later date they returned to the Sunderbunds (in then East Pakistan), this time concentrating on documentary filmmaking. In 1959, between her second and third books, Betty visited the area being flooded (in then Southern Rhodesia) by the new Kariba Dam where Stewart was working. Here she made a documentary film of the effects of the flooding on wildlife - Logging in the Sundarabans, East Pakistan - and wrote the story of a colourful Scottish Game and Tsetse Supervisor called Joe McGregor Brooks entitled Elephant Valley (1962).

Just prior to this trip Betty worked as a publicity officer for the Edinburgh Zoo and as with everything she did, she made use of this experience in her only work of fiction, Murder in the Zoo (1974).

Betty had a great zest for life, travel, cooking, uisge-beatha and good company that continued into her old age, becoming computer literate on her 90th birthday and spending her next 5 years, right to the end, sending and receiving emails from her family and many grandchildren scattered across the globe. During this time she also began putting together the text for her final publication, her memoirs, which, alas, she never finished. Betty was an only child and it never ceased to astonish her that she had so many descendants. Betty died quietly in Elgin on the 7 th November, just eight weeks after celebrating her 95th birthday with most of her immediate family. She is survived by her four children, thirteen grandchildren and eleven great grandchildren.